Aaand… back to regular scheduled programming. The past month has been pretty overwhelming with writing assignments, seminars, cross-Atlantic flights and the like. Now I’m back in my Costa Rican garden and a somewhat more relaxed schedule, and have so much to talk about up my sleeve! Thanks for the patience.

As a group, the Mercator fellows and alumni tend to think rather… international. We talk with enthusiasm about the Iran nuclear deal, how to bolster security in Afghanistan and stop fighting in Ukraine, how to solve the water crisis in Asia and create new markets for African enterprise. So it was slightly anathema to be invited to consider our very local, and personal climate impact, when visiting the Prinzessinnengärten in Berlin. I may have been the only one with a huge smile on my face since the visit catered so perfectly to my interests.

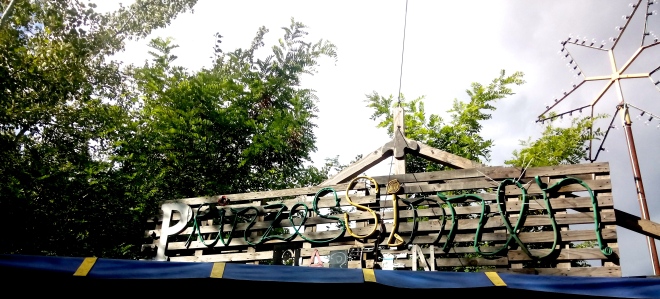

The gardens were founded in 2009 by Robert Shaw and the Nomadic Green initiative. Inspired by urban agriculture in Cuba, Shaw wanted to replicate this system of community building, face-to-face communication, learning and connecting in his home town. Getting to today’s exuberant medley of pots and crates brimming with plants, sheds filled with building material, corners for beekeeping and compost-making, and a vibrant community of guests and volunteers wasn’t easy.

The gardens were founded in 2009 by Robert Shaw and the Nomadic Green initiative. Inspired by urban agriculture in Cuba, Shaw wanted to replicate this system of community building, face-to-face communication, learning and connecting in his home town. Getting to today’s exuberant medley of pots and crates brimming with plants, sheds filled with building material, corners for beekeeping and compost-making, and a vibrant community of guests and volunteers wasn’t easy.

It took many negotiations with the city to get a long-term lease of the land, and one of the lease conditions was that nothing permanent be built. Thus, all the plant crates, sheds, café infrastructure, and even the tiny house that a group of entrepreneurs built could be removed at a moment’s notice and taken to a new home. This makes the Prinzessinnengärten unique in their approach to community-building: my impression was that they see themselves rather as an incubator and knowledge-generator, open to move on to communities in greater need once they have served their purpose where they are.

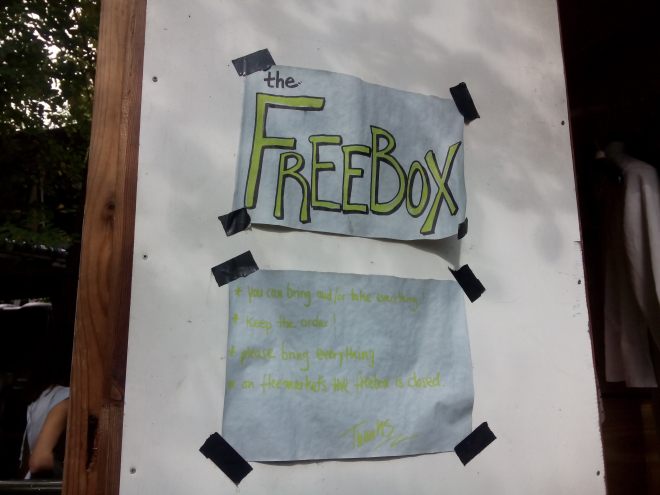

Indeed, one of the greatest advantages of the gardens is that they bring together like-minded people. You see the seeds of creative ideas everywhere: the giving-seeking board where you can provide or request services; the blackboard announcing workshops and talks; the shed of used clothes and items free for taking; or the recycling group which helps you to repair or reuse things you would’ve otherwise trashed. And you get to actually work with and get to know your neighbors – something that is surprisingly difficult in today’s digital era.

It’s definitely a particular mindset that is supported, though. Giggles erupted when our guide showed us the “worm factory” where compost-supporting worms are fed; and comments like “but couldn’t they tidy the place up a bit?” were common-place when discussing the decentralized set-up.

It’s definitely a particular mindset that is supported, though. Giggles erupted when our guide showed us the “worm factory” where compost-supporting worms are fed; and comments like “but couldn’t they tidy the place up a bit?” were common-place when discussing the decentralized set-up.

The importance of those aesthetical preferences fades however when you consider the real contradiction between the lifestyle ideas of the Prinzessinnengärten – highly localized, focused around small footprints, sufficiency and non-materialism, and the creation of long-lasting social ties – and the reality of many careers in international relations – strongly reliant on airplane transport, a regular relocation connected with the replacement of everyday objects, and social ties that are extremely international, often only possible through digital aids, and prone to frequent changes.

Can one combine those two lifestyles? The following day, we talked about that topic in more depth: about emissions compensation of airfares, choosing the train over the plane even if it costs you another day away from home, trying to participate in local initiatives even as an outsider and even for limited amounts of time. There are definitely easy choices one can make: which bank you save money in and how it’s invested; where you buy your food and what you consume; or how you choose to get around in everyday life, considering the options you have. Maybe your organization is committed to more videoconferences instead of constant business trips.

Can one combine those two lifestyles? The following day, we talked about that topic in more depth: about emissions compensation of airfares, choosing the train over the plane even if it costs you another day away from home, trying to participate in local initiatives even as an outsider and even for limited amounts of time. There are definitely easy choices one can make: which bank you save money in and how it’s invested; where you buy your food and what you consume; or how you choose to get around in everyday life, considering the options you have. Maybe your organization is committed to more videoconferences instead of constant business trips.

But a lingering doubt remains. I can’t shake the feeling that a truly international life cannot be a truly sustainable one. We were reminded by one participant to pick our battles and focus on the thing that we can add most value to; but what if sustainability is that battle?

At the airport bookstore, on my way back to Costa Rica, I picked up a magazine that had “sufficiency lifestyles” as a central theme. It portrayed a woman that gave up her career as a primate researcher to work on a farm in Germany producing her own food; she said that it gave her greater satisfaction, also because she didn’t have to struggle with feelings of hypocrisy. She, for herself, decided that the second purpose was great than the first. But is anything won if another person takes up that spot flying around the world, researching gorillas, other than a greater feeling of personal righteousness? And is that enough?

At the airport bookstore, on my way back to Costa Rica, I picked up a magazine that had “sufficiency lifestyles” as a central theme. It portrayed a woman that gave up her career as a primate researcher to work on a farm in Germany producing her own food; she said that it gave her greater satisfaction, also because she didn’t have to struggle with feelings of hypocrisy. She, for herself, decided that the second purpose was great than the first. But is anything won if another person takes up that spot flying around the world, researching gorillas, other than a greater feeling of personal righteousness? And is that enough?

Another interview was with Niko Paech, a leading proponent of the degrowth movement. He’s flown exactly once in his lifetime, and doesn’t own a car or even a microwave. I believe that it is precisely by virtue of those facts that he is taken so seriously. On the other hand, he is reliant on media – both his writing and telecommunications – to make his voice heard in the places that he has chosen to never visit. Case in point: the one I linked to above is the only interview in English I found, and it’s on a rather obscure alumni website. Also, he’ll never visit, never experience many places. Is that sacrifice worth it?

I don’t have a good conclusion to end this stream of thoughts on, particularly because I still haven’t come to my own conclusion. One thing I do think is that there are no easy win-win solutions; similar to the debate around families and careers, I think there is a choice to be made. “We can have it all”, it seems to me, has been a mantra that misleads energy and creativity for furious debates that could be used for finding compromise solutions. What that choice is, and that solution, depends on personal priorities and ethics. But who will make the hard choice first?

What do you think? Is it ethical to lead an unsustainable lifestyle to lobby for sustainability?

First of all, thanks for sharing! I stumbled across your blog a few weeks ago and have been really enjoying your posts. I really enjoyed reading the Niko Paech interview as well and was really struck by his idea that austerity is really relative and that it would depend on a person’s desire for material self-realization. He’s really brilliant and it was very thought-provoking to read, so thank you.

I think that the answer to your question about ethics and sustainability is something that would probably change over time. It seems like with the examples of people that you mentioned, Mr. Paech and the primate researcher, although at the beginning of a career it seems more important to fight the sustainability battle in one way, things change over time. I think being conscious and transparent about what you’re doing as you’re doing it will help you make the right decisions. As long as you’re fighting on the side of sustainability, you’re in the right place.

-Shelby

Thanks for your thoughts, Shelby! You’re right that it’s relative, and I like the thought that things change over time. I guess the golden middle and making conscious choices is the way for me to go right now. Thank you for reading!