The Protests

Smoke billows up between the sleek high-rises of the European Quarter in Brussels. The European milk farmers are angry, very angry. Many of them fear for their survival. After 31 years, the European Commission decided to end milk production quotas, to the dismay of many small and mid-scale producers. What with the Russian import embargo and a spike in production, prices have fallen dramatically – by 30% in the last year. But is this just complaining at a high level? Or are these serious concerns?

“There was agreement in the meeting that a widespread culture change is needed within the food supply chain to ensure that farmers see a fair share of risk and reward. The government and devolved ministers need to deliver on their promises, work together to achieve this culture change across the supply chain and to see real understanding of the cost of production to farmers.”

Arguments against Quotas

The EU’s management of its agricultural market has long been a point of contention for liberals. “The distortion of free markets leads to inefficiencies” – this is an unquestionable fact for agricultural economists. Let’s unravel the economic jargon:

The ideal scenario for economists is when the production of agricultural goods is exactly equal to demand. Then, in theory, the price of milk that consumers are happy to pay is exactly equal to the price that farmers are happy to receive. “Inefficient” farmers – those that are too small, that don’t use the right equipment, or don’t have the right skills – will drop out of the market, and the ones that survive are the ones that can produce most cheaply. The most efficient. The best.

State-led management interferes with this process. Quotas hold prices ‘artificially’ high, according to critics, and thus hurt consumers. Also, deciding who gets the quota – which countries and which producers – is complicated and expensive. “Producer rents” – the profit above production costs – are popular with farmers, the argument goes, and their distribution is akin to giving out political favors. Why should we subsidize farmers that cannot compete in the global marketplace?

“We’re going to take advantage of the opportunities that the abolition of milk quotas gives towards enhancing the potential of value-added processing which will create a lot of jobs and growth in rural areas,” [EC Agriculture Commissioner] Hogan said. “We have new market opportunities … particularly in the Far East,” he added.

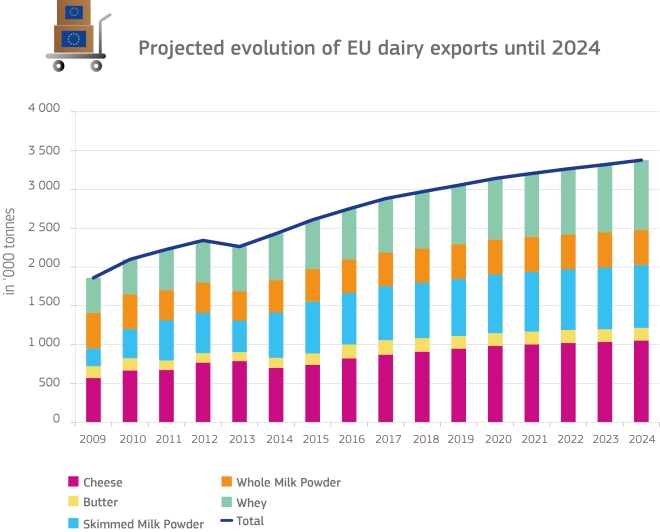

Initially, the most efficient European milk farmers, in Germany and Ireland, agree. Obviously. Lifting their production limits, they hoped, would lead to the possibility of expanding their exports to other regions of the world. Now, however, even German farmers are outraged that “milk currently is cheaper than water” and blame the European Commission for the faltering trade relationship to Russia where much of their exports were supposed to go. In addition, the Chinese economy did not live up to its potential. This, proponents say, has nothing to do with the quota, which had also failed at preventing low prices. Instead, it’s a short-term demand shock that will soon be remedied. No larger-scale reforms needed.

Arguments for Quotas

Somerset dairy farmer James Hole said: “All they are going to end up doing is create huge milk pools coming out of Europe. Long term there will probably have to be another form of capping. I can’t see how they can just make it a free-for-all.”

This, however, isn’t the entire story. The problem with agricultural markets is that they do not follow textbook theory. For one thing, once quotas fall away, each individual producer will want to produce more to increase his bottom line. When demand stays the same, prices fall. Theory says that farmers should then produce less. But what would you do if your profits start to decrease and decrease until you cannot keep up your loan repayments? You start producing more to gain at least a bit more. Then prices decrease even more. Then you go to Brussels and start clamoring for political support.

The farmers’ beef (almost literally) is this: In the globalized market today, “inefficiency” is always relative. Whom should European farmers have to compete with? With whose wages? With whose land prices? Whose production costs? Whose animal welfare policies? And whose demand should they try to fulfill? Why do faltering trade relationships with Russia have to spell the end of a small Austrian mountain farmer who just wants to make some local cheese?

The race for efficiency is almost always a race to the bottom. The bigger farms that use more intensive practices will have lower per-unit costs; if the price falls and falls, they will be the only ones that can survive. The reality of “efficiency” adjustments in economic theory is the foreclosure of farms, the loss of existence of entire families, the erosion of rural economic activities. This is the sad reality of today’s prices: By now, they are below production cost of all but the biggest corporations. No wonder there are protests.

Speaking at the EU Milk Market Observatory on 28 July, chair of Copa-Cogeca Milk Working Party, Mansel Raymond, argued that without EU action many producers would be forced out of business by winter. “The market is in a much more perilous state than it was four weeks ago, with producer prices far below production costs. It’s a critical situation for many dairy farmers across Europe,” he said.

Short-Term Fix or Long-Term Management?

Yet, the economic-political climate is clear: a return to production quotas is not an option. Instead, the plan seems to be to appease farmers with short-term fixes, including the release of €500 million in emergency funds, to be spent on “direct payments to farmers, covering the cost of storing skimmed milk powder, as well as on promotion of dairy and pork exports, an EU spokeswoman said”.

This is cheaper than administering a quota system? Or cheaper than just adding a couple of cents more per liter in the grocery store? Also – as we are gathering in December in Paris to discuss global climate goals, we are subsidizing one of the most greenhouse gas-intensive agricultural sectors to produce more than anybody even wants to consume and spend more money to convince more people to buy it?

In my eyes, this type of crisis will continue to happen as long as we are trying to find a demand-supply equilibrium that lies below the real price of goods.

It’s a terribly cruel way to balance a market by anticipating ‘market exit’ of some producers – when you strip the econ talk, that translates to bankrupcy. ‘Efficiency’ often translates to ‘intensification’, ‘corporate agriculture’ and – in many cases – the treatment of animals as production units instead of living beings. Is that the European agriculture we want?

I don’t want to defend the now-defunct quota system in its entirety – knowing EU regulations, I am sure it was plenty of red tape, and possibly also linked to political favoritism and tug-of-war.

However, no market management is no solution in my eyes.

I hope the Agriculture Ministers take this protest as an opportunity to think this through, and lay out long-term suggestions how to prevent, instead of fight, the next crisis. Not that we’ve shown a good track record in the past, though. But one can always hope. Quo vadis, future milk policy?