I can’t forget the wistful stares. “How lucky you are to come and visit us! We’d like to travel as well and see the world.” Legally, there is no problem anymore since the exit visa requirement was abolished in 2013. Yet, economically it is impossible for the vast majority of Cuban citizens. Average public-sector wages are around 500 Cuban pesos. At an exchange rate of 1:25 to CUC, the convertible ‘hard’ currency equivalent to 1 US$, most Cubans make $20 a month. Not enough for many imported luxury goods; not enough for a passport (which costs $100 alone); not enough for a plane ticket from the island. Not enough.

It was a very special experience to attend a conference on Development and the Environment in a place where, by virtue of ideology and necessity, human development has progressed with the almost complete absence of consumerism. Rather, traces of ingenuity in repairing 60-year-old cars and machinery, of mutual assistance in the face of adversity and of sarcastic but yet somehow genuine joie de vivre are everywhere.

“We are Cubans, but we are happy anyway!”, I am told when walking along the rocky shoreline on the outskirts of Havana where local youth gather. And yet, in many instances the enthusiasm Cubans show for chatting with foreigners has a palpable tinge of desperate hope – maybe this connection will be my ticket out?

Almost everyone I talk to wants to leave. The graduate researchers investigating marine ecosystems, for a PhD in Brazil. The former cyclist turned taxi driver, to join his sister in Miami. The young friends sharing a drink with us at the Malecon, to live with their significant others in Germany and Holland. The exodus of young professionals, the brightest and smartest of their generation, already at record levels in 2010, is continuing. And who can blame them?

What is most disconcerting to me is the consistently high level of education, culture, and knowledge that I come across that is so at odds with the limited economic opportunities available to the people. Maybe seeing this as a contradiction already betrays my growing up in a capitalist system. As a report on Cuban labor markets highlights,

The forces that shape the formation of skills in market economies result in a strong relationship between education and earning potential. Such a close relationship need not exist in Cuba, where the process of skill formation has been very different.

Cuba has 2% of Latin American population, but 11% of its scientists. In 2009, it ranked first in the education component of the Human Development Index, and very close to the top regarding life expectancy. Yet, its low per-capita income lowered the HDI score (#50 overall), leading to interesting conclusions:

Cuba is ranked 95th in the world in GDP per capita. The gap between its low GDP ranking and much higher overall HDI ranking reveals its human development is significantly higher than its GDP per capita might indicate.

The difference between these two rankings can be seen as a measure of the efficiency of converting a nation’s income into the health and education of its people. Cuba heads the world in this category, by a wide margin.

While the labor market report focuses on the inefficiencies of such a system and the changes necessary for a transition to a market economy, you could embrace the dichotomy as well.

After all, isn’t this a post-growth dream scenario? Developing the basic human rights – to sufficient food, health care, education, and meaningful work – ahead of all others and redefining value in terms of human knowledge and fulfillment rather than in terms of material production could reasonably be seen as the low-footprint development path our societies should emulate in a resource-scarce world.

Coming from Americanized Costa Rica, with its ubiquitous McDonald’s, Taco Bell’s, KFCs and a strong consumer culture, it is a step into another world with no private advertisements, no international chains, no shopping malls.

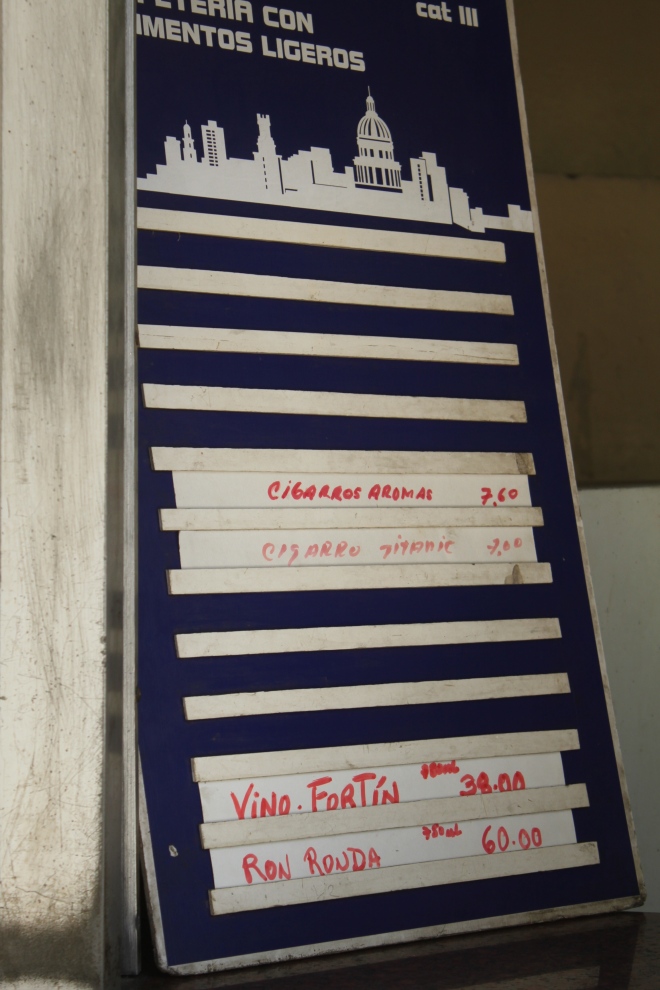

And yet, and yet. “A bit more materialism would be extremely welcome here”, chuckles the young agronomist to whom I try to explain my feelings, caught between nostalgia, idealism and empathy for the inconveniences and injustices suffered daily. Walking into side streets, you see stores that are half empty, carrying rather haphazard combinations of goods – in one memorable example, one shelf of toothpaste, some canned vegetables, and a wall of liquor. Many stores have menu boards with little slates where they can adjust what they have on offer at any given day.

Clearly, this level of access to consumer goods is still too restricted. Another acquaintance demonstrated to us how many years one would need to save to afford a refrigerator if you don’t get an underhand deal like he did. I am pretty sure it was multiple years.

The double currency system exacerbates the problem, because it makes it painfully obvious to Cubans how little value their work has in an international context. The $20 are sufficient to get by on Cuban goods, but any type of tourist amenity – a hotel, a cafe, a nightclub – is off-limits or a very rare treat for Cubans that are paid in national pesos. On the flipside, once you work in the tourist sector and are paid in CUC, the situation changes dramatically and a taxi driver can easily make up to $80 a day. Of course, this type of inequality is poison for morale, and it is likely to become even more pronounced as Cuba opens itself up to more US tourism.

Now, certainly there are basic needs in Cuba that are still unfulfilled and where some development is direly necessary. Yet, beyond that, this is one of the last vestiges of the world where humanistic values – of full employment, of freely available education, of support for sports and the arts – were put front and center in government policy and traded off against a consumer society. A Mexican friend was commenting that, while Mexico knows similar pockets of poverty, entering the labor market is much more complicated and competitive, and it is very rare indeed that you find a job you really care about doing. And one only has to look at the billions of student loan debt in the United States to understand the value of free education.

Very similar to the situation between East and West Germany, it seems many Cubans underestimate the significant advantages of their system while looking to their Western visitors (those who can afford to come!) as role models of where their economy should go. Yet, I would hesitate to make this argument in a face-to-face discussion because their discontent deserves to be taken seriously.

I wonder about the lead cause of the immense frustration Cubans experience: is it the level of control over their life decisions still held by the government? Is it the small exchange value of their work? The low standard of living in absolute? Or rather the comparison with international visitors?

Surely it is a mute point, as it is likely to be a combination of all of the above and then some. But when thinking about future sustainable societies and the human experience, it becomes relevant. Thorsten Veblen, a 19th-century economist and philosopher, coined the term of “conspicuous consumption”, of consumption beyond one’s needs as a path to gain social status and reputation. Other consumption theories highlight the drive for (over)consumption as a way to construct one’s personal identity, to signal one’s attractiveness to potential mates and rivals, and – one of the most interesting ideas in my opinion – to fight against the finality of human mortality. Since our society is increasingly secularized, so the theory goes, we are losing the certainty of some sort of continuity after death which previously was guaranteed by religions through heaven, nirvana, or rebirth constructs. Now we need to pack all experiences we certainly want to have into one lifetime; overconsumption is the unavoidable consequence.

If this is indeed the human condition, and we intrinsically place value in consumer goods such as smartphones, flatscreen TVs, brand clothing and airplane travel, I don’t see how we can grow as a human population without destroying the planet. Once the potential for such a ‘rich’ life unleashed, who would be happy with less?

If I had access to the things you have, and could come visit you in your country as well at will, I’d be the best Communist. Communism, capitalism, we don’t care – we just want to live!

Similarly, I think Veblen’s thinking also plays a large role. I have experienced Cubans as an incredibly proud and dignified people. The self-awareness of being seen as ‘poor’ by Western visitors, I felt, might be much more pronounced due to their level of education and contact to the rest of the world. Their status and value structure, despite all education and propaganda attempts, is still similar to our own, and still tied to their purchasing power. Comparisons are easily made at every turn, and how do you really convince yourself that your country’s contributions and people are just as valuable and important members of the world community if you keep encountering pity from well-meaning foreigners?

This makes the Cuban experiment so powerful, and yet so heartbreaking. Because as much as Communism struggles to survive in a globalized, neoliberal market system, I fear that low-impact, sustainable living will have problems to develop within these surroundings.

As long as the current tenor of ‘more is more’ doesn’t change, it takes an incredibly strong-minded group of people (or nation) to go against the grain of ‘human development’.

In any case, it will be fascinating to see how it opens up. I hope it will be able to avoid past mistakes, of which there have been many, and keep its basic humanist guiding principles alive while giving people greater political and economic opportunities.

What do you think about the Cuban project?