When we visited the UN Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights (OHCHR), they received us with smiles full of passion, but also visibly exhausted. In this country, trying to ensure the protection of political, economic and social rights with a staff of six and a minuscule budget could seem like a quixotic battle. One of the issues of greatest concern to them is the ongoing lack of land titles, and the subsequent uncertainty and missing legal recourses for subsistence farmers that are being replaced by powerful agribusinesses.

The issue of land titles emerged, as so many of Cambodia’s woes, during the Khmer Rouge period. The forced collectivization and ruthless shift to an agrarian socialist utopia obliterated private claims to land; during their time of rule, between 1975 and 1979, the Khmer Rouge also destroyed all land records, leaving no documentary trail of who owned what before the period of upheaval.

Once the Khmer Rouge rule – which also killed around 1.7 million people through starvation, disease and political executions – was over, people scrambled to settle wherever they could and begin a new life in the wake of immense tragedy. Often having relocated multiple times with the clothes they were wearing as only possessions, official documentation was unheard of. This made – and makes – the settling of disputes over land extremely complicated.

In 2001, the “Land Law” of Cambodia was passed, which allows any person that had been living peacefully on a piece of land for five years to apply for a land title. A second part of the law, however, was the one authorizing “economic land concessions”, where governmentally-owned land can be leased to corporations (mainly agri-businesses) for a period of up to 99 years. Furthermore, “social land concessions” are supposed to transfer state-held land to disadvantaged and poor communities, and “communal land titling” theoretically allows for indigenous communities to apply for a communal rather than a private title.

In theory, at least, Cambodia thus has the legal framework in place to overcome the legal uncertainty regarding land titling. Also, this issue has been in the focus of donor countries, and development agencies and NGOs both have initiated projects that support land titling. Yet, particularly individual land titling is a sisyphus-esque task which takes considerable amounts of time, such that only parts of the country have yet been reached. At the same time, economic land concessions go forth on land that could have also been claimed as individually owned – since there has been no formal assessment of what really is “state-owned land”, in many instances land concessions formalize ownership by default. It thus seems to be a “first come-first served” system, where whoever shows up first with a claim on a piece of land is likely to be heard.

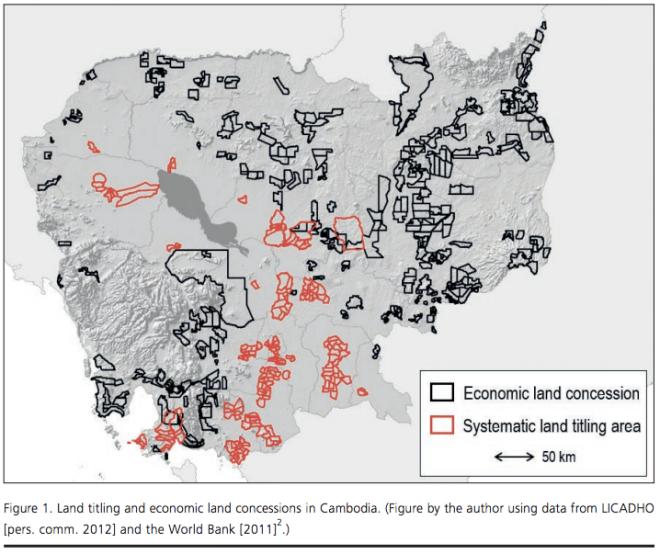

This makes the decision where individual land titling efforts are being initiated all the more relevant. An interesting policy brief by the University of Berne has contrasted the areas of land titling projects with those that economic concessions are ongoing. Lo and behold the map:

As they explain, there are clear advantages for starting systematic land titling initiatives in relatively uncontested areas: the political pressure is less, accommodation of economic interests within an area can contribute to economic development, success is more likely, and since land titling employees are often rewarded by number of titles or area covered, there are also strong internal incentives to start in densely populated but uncontested areas where titles are already de-facto existing.

However, this completely contradicts the presumed purpose of systematic land titling, namely the protection of individual social and economic rights in the face of powerful contrary interests. Stories abound of farmers and property owners that were disowned and resettled due to an economic land concession without legal recourse because they had no official claim to the land they had settled on or bought from a previous settler.

Similarly, the social and communal land transfer options laid out in law have had very limited success. According to reports, only 1% of concessions of state-owned land were of the social variety, while the overwhelming majority was given to companies. Furthermore, the fact that communal land titling is restricted to indigenous communities excludes many groups of Cambodians that use land collectively, for example as pasture land. Also, bureaucratic hurdles mean that only a handful of communal land titles have been granted so far.

Thus, I feel like the authors of the policy brief have a good point when they argue that implementing land titling initiatives is not enough – it needs to be targeted to where it can actually make an impact on people’s rights and livelihoods. This also means altering metrics of success:

If meant to enhance tenure, titling campaigns require metrics that accurately reflect that aim. “Impact” in such a context would mean safeguarding vulnerable land users’ access to resources, and might draw on conflict- rather than area-based indicators.

Further reading, if you are interested, could be the reports of the Special Representative of the Secretary General for Human Rights of 2007 and 2012.