... how would you finish that joke? Unfortunately, for Costa Rican farmers, this issue is no laughing matter. Rather, it’s a conflict that pitches two of the largest agricultural communities of the country against each other in a perpetual feud. It’s the yeoman-versus-rancher battle you’ve never heard of. But new technologies might offer a solution that also contributes to Costa Rica’s climate change strategy.

In fact, this is how I first became aware of the story: I was co-organizing a workshop on the use of organic agricultural residues in energy production. Reps from all kinds of industries – pineapple, sugarcane, coffee, livestock, forestry – came together and talked about possibilities and hurdles to actually use the energy potential of these waste products. One of their activities was to brainstorm co-benefits of changing waste disposal practices. I was tasked with documenting the workshop and so spent my time weaving in and out the intensive discussions. Between snapping photos, I snatched up snippets of conversation. “Oh, and getting rid of the pineapple stems also reduces the flies!,” I heard. Makes sense, I thought to myself, fruit flies are icky. Little did I know that the issue was much more dire than just fruit flies.

Back at the office, I got confused again while writing the event summary. “What exactly is the deal with the flies?” My co-worker sighed. “Oh, it’s the biggest conflict between livestock holders and the pineapple plantations. If you leave the pineapple stubs on the fields, it attracts these bloodsucking flies and they bother the cows so much they stop giving milk.” This explanation was so intriguing, I just had to do more research.

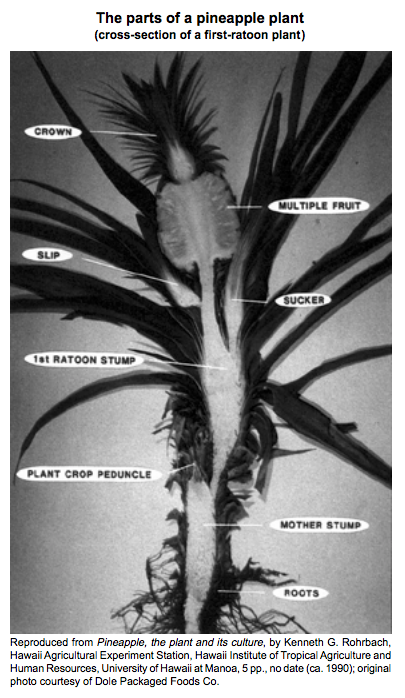

After banana production, the pineapple industry is the second most important agricultural export of the country. In fact, three quarters of pineapples sold in Europe come from this country the size of Denmark. The production is characterized by high-input, large-scale monocultures. As the pineapple is a bromeliad, each fruit grows on its own stem. Each plant will typically give two fruits, at 15 and 27 months after planting. At harvest, the stubs are typically left on the ground, and need to be eliminated after the second harvest. Due to their conical shape, they are the perfect receptacles for rainwater to pool and provide breeding grounds for insects – foremost, the mosca “chupasangre”, the blood-sucking stable fly (Stomoxis calcitrans). Each fly can multiply by 3.500 when laying its eggs in the decomposing plants. The flies feed five times a day, apparently because they regurgitate the blood they already ingested at regular intervals (ugh!). Nearby cattle farms thus see their pastures infested with swarms of the flies, which turn their cows lethargic, unwilling to eat, and seriously affect milk production.

This problem has been going on for decades – the Tico Times reported on the issue back in 2005, unveiling that the flies suck off “an average of one kilogram of weight from each animal every day” (which sounds pretty incredible but then I guess it depends on the amount of flies?). In 2008, it was taken up again by a local newspaper, which cited losses worth “millions” for the cattle industry. Milk yields can drop by 40 to 50% in cows too agitated to feed properly and who stay in their stalls rather than venture out to graze. Furthermore, their injuries can get infected and provide entrypoints for viruses and bacterias. The flies don’t stop at the cattle, either – the articles also speak of locals that are exasperated by the constant insect attacks.

These economic as well as environmental problems have led to many confrontations between dairy holders and pineapple plantations, which are frequently owned by multinational or large national corporations. The pineapple farmers say that they do their share in disposing of the agricultural waste. This mainly consists of applying herbicides in order to dry the stems (which creates a host of different environmental issues), and their subsequent incorporation in the soil. In other contexts, pineapple stumps are burned off, and the char is incorporated back into the soil as well.

However, this problem can also be seen as opportunity: since unsellable biomass makes up 50 – 65% of the plant, growing pineapples is inherently a wasteful business. If all that biomass – an estimated 13 million tons annually – were to be put to use in energy production, not only could its label as “waste” be rethought, it would also replace fossil fuel energy sources. Currently, the waste is mainly left on the fields because it’s seen as worthless and taking it in would incur losses for farmers. Transforming the biomass into methane gas that can then be used for heat or electricity generation would not only save the companies money in energy expenditure, but also potentially their neighborly relations to their dairy friends. Now that’s what I call a co-benefit!

Black Soldier Fly Larvae (BSFL) can solve the problem in 2 ways… First they will consume the pineapple waste quickly and organically.

Second, they tend to drive away all other flies.

They are raised as chicken, duck and fish fodder in rural U.S. with no noticeable human aggravation.

Composting with both worms and BSFL also leaves secondary bio-media like compost, worm castings and BSFL Castings that an be spread on the fields as fertilizer.

Also, adding chickens free ranging the fields between harvesting and replanting times will reduce the larvae of the ‘the mosca “chupasangre”, the blood-sucking stable fly (Stomoxis calcitrans)’ dramatically!

http://ourmountaingrowers.com/

Jason Brown

Huh, that is so interesting! Our next workshop is on using biomass as a fertilizer so I’ll make sure to bring up the topic of BSFL! Thanks for your comment!

Reblogged this on fiifaelite.