Philanthropy is an interesting concept. Here is one person, or a board of people, with more money to distribute than small nations have budgets. If they choose to concentrate on a topic, their impact can be immense and drive research, NGO actions and government policies in the direction of their liking because of the financial incentive. What a responsibility.

The NGO Grain decided to check on that responsibility and have a look at where the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation spent their money. The Guardian (hilariously – look at who they are sponsored by) reported.

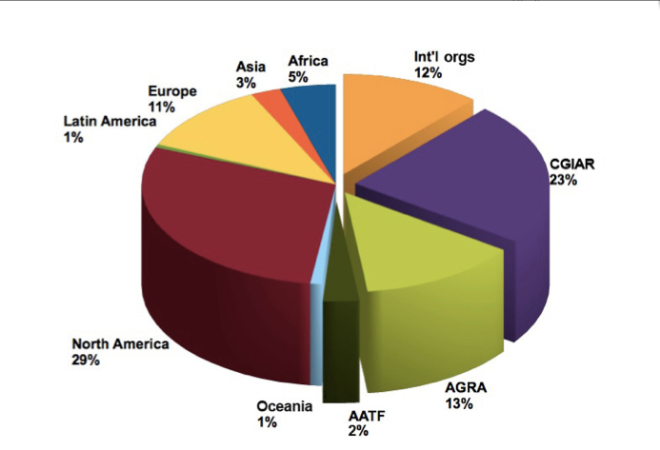

Isn’t that interesting? Of course, development spending can occur in a variety of ways, but it is striking nonetheless where the Gates Foundation thinks most support is needed. And they have become a massive player in supporting agriculture and food issues, with more than $3 billion to date given to various organizations.

Almost a quarter goes to the network of agricultural research centers CGIAR. According to Grain,

“In the 1960s and 70s, these centres were responsible for the development and spread of a controversial ‘green revolution’ model of agriculture in parts of Asia and Latin America which focused on the mass distribution of a few varieties of seeds that could produce high yields – with the generous application of chemical fertilisers and pesticides.

“Efforts to implement the same model in Africa failed and, globally, CGIAR lost relevance as corporations like Syngenta and Monsanto have taken control over seed markets. Money from the Gates foundation is now providing CGIAR and its green revolution model with a new lease of life, this time in direct partnership with seed and pesticide companies.”

Another big chunk funds AGRA, the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa, which was set up by Gates himself; international organizations like UN agencies and the World Bank, and the African Agricultural Technology Foundation.

The rest of the money is distributed to hundreds of service-delivery NGOs. This, according to the report, was the largest surprise: “The north-south divide is most shocking, however, when we look at the $669m given to non-government groups for agriculture work. Africa-based groups received just 4%. Over 75% went to organisations based in the US”.

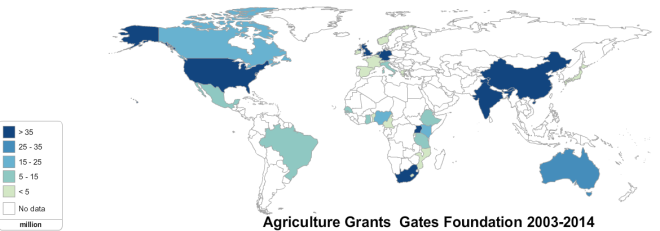

Grain also published this map which makes the divide even more visually apparent:

Now, some of this information may be oversimplified, since the European and US-headquartered organizations include NGOs like Oxfam, CARE, or Heifer Project, most of which implement projects on the ground.

And yet… much of this money does remain within the West, whether through Western NGO workers’ salaries, the overhead of the headquarters, or the influx in funding for Western universities. Imagine the positive multiplier effect if $3 billion had been spent on African universities, African NGO wages, and African ideas.

This is, in a nutshell, what Grain has the most problems with – the fact that the entire funding scheme seems to ignore on-the-ground knowledge and solutions and continue to focus on a top-down, scientist-driven and highly elitist way of solving global issues.

“We could find no evidence of any support from the Gates Foundation for programmes of research or technology development carried out by farmers or based on farmers’ knowledge, despite the multitude of such initiatives that exist across the continent. (African farmers, after all, do continue to supply an estimated 90% of the seed used on the continent!) The foundation has consistently chosen to put its money into top down structures of knowledge generation and flow, where farmers’ are mere recipients of the technologies developed in labs and sold to them by companies.”

This approach, sadly, is also much of the reality that exists within the Eurobubble so far. Much is made of improving seeds, improving infrastructure, and ‘climate-proofing’ agriculture through innovation. However, innovation is frequently seen in a very narrow sense. Grain again:

“Listening to farmers and addressing their specific needs” is the first guiding principle of the Gates Foundation’s work on agriculture. But it is hard to listen to someone when you cannot hear them. Small farmers in Africa do not participate in the spaces where the agendas are set for the agricultural research institutions, NGOs or initiatives, like AGRA, that the Gates Foundation supports. These spaces are dominated by foundation reps, high-level politicians, business executives, and scientists.

Listening to someone, if it has any real significance, should also include the intent to learn. But nowhere in the programmes funded by the Gates Foundation is there any indication that it believes that Africa’s small farmers have anything to teach, that they have anything to contribute to research, development and policy agendas. The continent’s farmers are always cast as the recipients, the consumers of knowledge and technology from others. In practice, the foundation’s first guiding principle appears to be a marketing exercise to sell its technologies to farmers. In that, it looks, not surprisingly, a lot like Microsoft.

This brings up again the whole food sovereignty debate and the question whether smallholder farmers’ knowledge and traditional methods are the future of society or a bucolic and sentimental dream of idealists. I think the answer lies somewhere in between; but if the odds are always stacked in one particular way, it’s hard to give both a chance.

Grain’s report can be found here; they also provide the spreadsheet they used for their findings online, which I liked a lot.

If local knowledge and skills could solve the problems, we would not be discussing this. While these are crucial,why should the benefits of research elsewhere be ignored? I am wary of anyone who would characterize the Green Revolution as controversial. I lived through it, without the transformation it brought to Indian agriculture, famines would have been inevitable. Any development program has its flaws, specially in hindsight, but shutting out advances in agricultural science is not the way to go and their location is not a huge factor. Yes, peasant farmers are not heard at conference forums but that holds for international as well as local conferences and meetings. That is a social and economic issue, unrelated to ag science. That is for Grain, but I want to say I enjoyed your take, specially the bit about the sponsors 🙂

Reblogged this on Dr. B. A. Usman's Blog and commented:

“This brings up again the whole food sovereignty debate and the question whether smallholder farmers’ knowledge and traditional methods are the future of society or a bucolic and sentimental dream of idealists. I think the answer lies somewhere in between; but if the odds are always stacked in one particular way, it’s hard to give both a chance.” – Food(Policy) for thought.

Reblogged this on AgroEcoPeople.