What’s better on a Sunday morning than brunch? A Fair Trade brunch! Oxfam Belgium is celebrating its 50 year anniversary (Happy birthday!) and invited the public to celebrate with organic and fair trade breakfast treats. An invitation my friend and I just couldn’t say no to!

The event was organized in a huge market hall, there was live music and speeches, and the buffet was plentiful – organic bread and rolls, diverse jams and spreads, cereal and yoghurt, frittatas and soups, cheese, fruit … The list goes on! Of course, all in fair trade quality. It was actually amazing to see the variety of items available now – there is nothing you cannot get with that label on it.

And of course, the fruit juices were the star of the show.

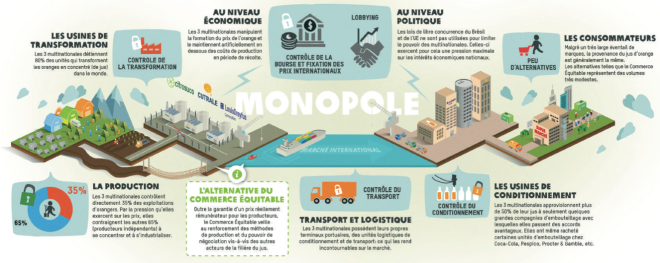

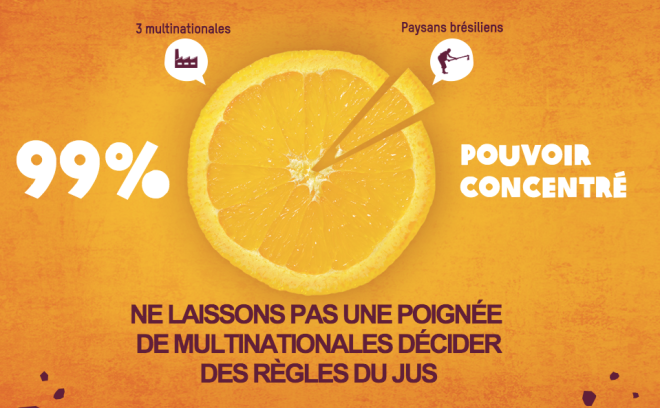

This because one of the purposes of the brunch was also to draw attention to Oxfam’s new campaign on the orange cartel. Did you know that the orange juice industry is basically shared by only 3 multinational corporations? These three (Cutrale, Louis Dreyfus Commodities and Citrosuco) dominate not only the processing and sales of the juice, but are present at every single level of production thanks to vertical integration. Together, they own:

- 35% of orange groves (and exert considerable price pressure on the other 65% of independent growers);

- 80% of processing facilities (which turn the oranges into concentrate);

- their own port terminals, transportation and logistical chains;

- and funnel more than 50% of the juice through a mere handful of bottling plants in order to retain control over the price and quality of the post-processing.

This also means that consumers have as good as no options when it comes to the quality or provenance of their juice (alternative products such as organic or fair trade still make out minuscule segments of the market) and often pay hefty prices for the juice despite the fact that the small-scale producers of the oranges are only paid a pittance.

In fact, Brazil is today the main producer of oranges globally (a third of the world’s production of oranges and more than half of all orange juice comes from the country), and the conditions of workers are so terrible that one lawyer said that “though the workers that harvest the oranges for these companies aren’t shackled like slaves, (…) other methods are used to hold them captive.” Such methods, for instance, are the use of market power to dictate prices so low they barely cover production cost (recently, around 2.60 Euros per crate (around 40 kg) of oranges was paid to producers. Calculations by economist Mendonça de Barros give a price of 3,40 Euro (9,64 Real) as a reference price that would allow farmers to at least recoup production costs). This policy drives many farmers to lose their fields and to become landless plantation workers.

How can prices become so low? There are two mechanisms at work: first, orange juice concentrate is traded on the New York Stock Exchange and prices vary dramatically according to harvest forecasts, demand and supply. The three corporations have also been accused of price manipulation at the Exchange, ensuring that prices drop during the harvest (when producers are selling to processors, and prices are fixed based on the stock exchange spot price) and stabilize shortly after.

Second, if you are only three, it is easy to work together and divide the market amongst yourself. From the former owner of CTM Citrus, Dino Tofini, whose juice plants were recently bought up by Citrosuco and Cutrale:

“We would meet every Wednesday and decide who we would buy from. Every firm had their own region. We divided the state of São Paulo between us. Cutrale was present throughout the country. Citrovita was more present in the Matoa region. We were more active in the Limeira region. Back then we would agree on a price of 3.20 dollars (ca. 2,40 Euro) per crate.”

This is the very definition of market power.

Working conditions in general are troubling since growing oranges is very labor-intensive. Most oranges are picked by hand, by farm laborers that travel from plantation to plantation in the search for work. There is a general atmosphere of fear from reprisals to even talk about the labor conditions. Those who did talk, mentioned precarious employment conditions and a lack of job security; seasonal contracts put continuous pressure to perform to the maximum or risk being replaced in the next season. As for the pay, a seasonal harvest worker earns on average nine Euro a day for picking around two tonnes of oranges, while a study by the Brazilian trade unions indicates that 14 Euro per day is the absolute subsistence minimum. Though there is an official workweek of 44 hours/week, in practice the expectations are so high that workers skip their lunch break and work through the weekend in order to fulfill their dues, giving them no time to recuperate. In addition, there are health concerns due to the widespread use of agrochemicals without due care and the focus on productivity that does not take into account illness or injuries of the workers.

Europe imports 70% of the traded orange juice from Brazil (one reason is that Florida’s production is mainly consumed domestically by Americans). Germany alone is responsible for 17% of all imports. When you are preparing your next Sunday brunch, why not consider a fair trade juice the next time?

For more information on the issue, check out the supporting documents on this site (several in French, one in English), this video (in French) and Oxfam Belgium’s campaign site!

One thought on “How Fair Is Your OJ? Fair Trade Brunch by Oxfam!”