When Dan O’Neill came to the required reforms of the banking system in his ISEE key note (which I resumed here), and used this image on his slide, I had never heard of the term ‘fractional reserve banking’. But if there is a cat meme on the topic, it is clearly a topic worth looking into, right?

Cue me going down the rabbit hole of trying to understand the way our current money system works, with the very valuable help of the guys at Positive Money. One caveat right away – the peeps explaining the system have focused on the UK, so there might be minor differences when looking at the EU or the USA, though Wikipedia tells me that fractional reserve banking is the current form of banking practiced in all countries worldwide.

If you have 2 hours at your hands, I would really recommend watching the video tutorial that Positive Money has made, it explains the whole issue much better than I will be able to picture here. But if you want a sneak peek in the problem and some of the solutions talked about at the conference… Read on!

Basically, think about how you imagine banks work. What happens when you walk up to a bank and deposit $100 of your hard-earned money?

a) They keep it in a big vault and wait for you to come and reclaim it.

b) They keep a certain percentage of it safe and lend the rest out to somebody who wants to loan money against an interest rate.

c) They take it, use it according to their best idea of what to do with it, and treat your deposit basically as an IOU (a requirement to repay you at some point) that they don’t necessarily have to be able to honor right now.

Decided? Read about the right answer after the jump!

So… a) is wrong. Surprise! We all know that if banks were just keeping saved money in the banks, there would be no possibility for investments to happen, or for interest to accrue. What is more surprising is that b) is (according to the Positive Money people) wrong as well, despite the fact that this is still the way banking is taught (in a stylized version) in economics courses.

What, economists are being taught concepts that don’t apply to reality? I know, shocking.

To get behind the problem attached to this wrong world view, we’ll have to backtrack a bit. And introduce the great issue that our current (fractional reserve) banking system introduces in the economy:

In our current banking system, commercial banks can create money.

What? Isn’t that the responsibility of the government, through the central bank? That’s what I thought, too.

And in the past, that was the idea, too, though rules and regulations have started easing up since the 1970s to make that system less and less applicable. Let’s see whether we can unravel that ball of yarn understandably.

The first thing we need to understand is that there are 3 different kinds of money: physical cash (which the central bank prints), central bank reserves (which are equivalent to printed cash but used by commercial banks themselves), and the numbers in your bank account. These are in banking jargon called ‘bank deposits’, ‘demand deposits’, or ‘bank credit’. But – and most importantly – they only have a limited connection to the money issued by central banks.

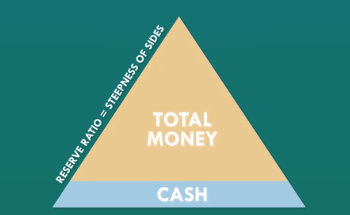

So far, we are still in our banking system b), since what is assumed to happen is the money multiplier model. Assuming that I come with $100 to the bank and the bank has to hold some percentage of that in reserves according to law (something called reserve requirements) – let’s say 10% – the bank will loan out $90 to a willing entrepreneur, who will deposit those 90$ in another bank, which will keep $9 in reserve and loan out $81, and the cycle continues until there is no more physical cash to go around. This can be pictured as a pyramid:

So there is a multiplying effect of the central bank’s reserves, but it’s limited by the reserve ratio. The government/central bank is still in control of the total money supply, either through changing the base of the pyramid (increasing/decreasing the cash circulating in the economy) or through changing the reserve requirements. All is well, right?

Except that reserve ratios are tricky. At least in the UK, there hasn’t really been a reserve ratio for years, and even when it existed, in the later years it was extended to ‘liquid assets’ – which includes government bonds. But government bonds can be bought and sold against cash, so the central bank-issued notes don’t remain in the reserves at all (which is the point of a reserve ratio), but go on further and further in the economy.

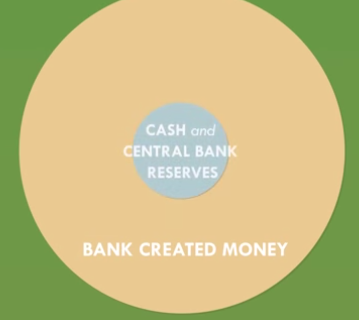

Eliminating strong reserve ratios equates to eliminating our pyramid model in favor of another one – the balloon.

Here, money is created by commercial banks extending loans (without any necessary cash base) to trustworthy individuals. In their balance sheet, they can log it as an asset (because they have the promise that the individual will pay back the money) and a liability (the IOU of having a certain amount of money in a checking account that they will have to pay out to the person when they ask for it) and have balanced books.

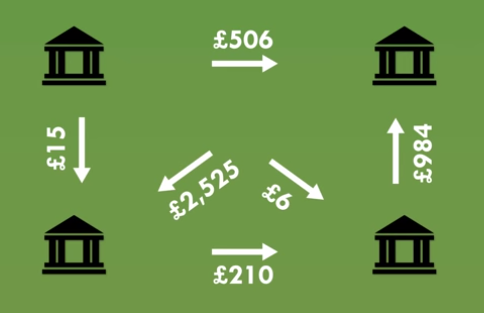

But, you will say, this system will come crashing down when these newly endowed individuals want to pay for things, right? How does the bank cover expenses that it has no bases for? This is where having a multitude of commercial banks comes in handy. Remember the second kind of money, the central bank reserves? This is the ‘real money’ banks pay each other with. But because there are so many transactions to and from banks, most of the charges effectively cancel out! So imagine: Bank A makes a loan of (effectively, ‘creates’) $1000 to Peter and Bank B makes one to Paula of $2000. Now, Paula pays her tuition fees of $1200 to her school which has an account at Bank A, while Peter spends his $1000 on electronics at the Apple Store, which banks with Bank B. Technically, bank A would have to send $1000 in central bank reserves to Bank B, and Bank B should send $1200 to Bank A. But that is silly – so they net out the differences and only Bank B sends $200 to Bank A. This is the way scores are settled between banks at the end of every day. Note that now Bank A technically doesn’t need any ‘real’ money to back up the $1000 it loaned out and Bank B only needs one sixth of the $1200 it created. Even if it didn’t have $200 in central bank reserves, because there is a set number of reserves in the economy it is as good as certain that another bank has an extra $200 that it can lend to Bank B.

Through this interbank settlement mechanism, the money supply can increase basically infinitely if all banks increase their lending at roughly the same rate and all are willing to lend to each other. However, this makes our system super vulnerable in a variety of ways:

1. In the case of a bank run, when people all demand their deposits back, banks are bound to collapse. That is, unless they are backed by the government, which will then act as a lender of last resort and reimburse people’s deposits up to a certain amount. Yet, this is financed by a pool of money from the banks, but if there is a general crash, one will have to resort to taxpayer dollars, and thus repay some people the money that banks lost with other people’s money. Unfair?

2. In the case of an economic crisis, when banks stop lending to each other because they don’t trust each other anymore (as happened 2008/2009), the whole system comes crashing down again as well.

3. Without effective reserve ratios, it is difficult for central banks to kickstart the economy again, as we noticed during the crisis as well. Pumping money into the base (quantitative easing) doesn’t have much effect as long as bankers don’t start to give out loans again, and that decision depends much more on their confidence in the market and the economy than on the base money available. In general, a system that relies on bankers’ confidence to create money will create too much money in good economic times and too little during recessions.

4. This also means that our economic growth is basically built on debt. And that if everybody paid back their debt, we would in effect shrink the money supply and go into a recession.

5. And what irks me most – resource use and unsustainable consumption behaviors then as well are basically built on debt and a totally fabricated idea of ‘wealth’ that is not really tied to that much value creation, is it? Gaaah if you think too much about it your mind gets all warped, eh?

So, what can we do about it? This is where ISEE was really inspirational. But maybe let’s talk about that in the next blog post, yeah?

One thought on “Fractional Reserve Banking – The Problems [ISEE recap 2]”