Well, after another couple of hours of editing (why does the final version always take so long to get consistent? And why did we nearly forget to include our most important source in the bibliography? Questions…) I finally sent off our Cost Benefit Analysis project to our teacher and thought that since my friend and I had put so much work into it, it’d be cool to share our results in a little more public way – for example, here!

For this project, the story begins around 2007 when Ecuador found its second-largest unexploited oilfield with estimated reserves of around 920 million barrel. The catch? It is sitting right under the region’s largest untouched rainforest, the Yasuni National Park, which is unrivalled in biodiversity – in one single hectare of the park, you’ll find more tree species than in all of Canada and the US combined; it harbors around one-third of the Amazon’s reptile and amphibian species in only 0.15% of its territory, and is home to several mammals on the brink of extinction.

Long story short, as I wrote before, the Ecuadorian government decided to give up on its novel project called the Yasuni-ITT Initiative, where it offered to leave the Yasuni untouched if the world community were willing to pay it part of its opportunity cost (the global community did not step up to the challenge) and announced in October that it would start drilling.

Our research question was whether this decision to commence drilling for oil in the Yasuni National Park is economically justified or not, if you take into account all the costs to society involved. To cut to the chase – it depends (economists’ favorite answer, ever). And cost benefit analysis (CBA) is complicated.

In order to do a proper CBA, you need to first estimate all impacts resulting from the project under consideration, then place a dollar value on each and every impact, and finally discount your results over time (we’ll come to that in a minute). If you’ve done everything correctly, in the end you will have a net present value of the entire project that is either positive or negative – depending on whether it would result in a net benefit or loss – and are all the wiser as to whether the project should be implemented or not.

Image by Flickr user sara_y_tsunki, via Flickr CC.

The easiest part was to estimate the benefits – stemming mainly from the oil revenues. However, already here we ran into significant trouble trying to predict accurate figures: both the actually exploitable resources (between 410 million and 1’531 million barrels) and the projected oil prices were subject to massive fluctuations which could influence the gross benefit of the project immensely.

This issue of uncertainty was only compounded when trying to estimate the costs. The easiest was infrastructure costs (though anybody that built their own house or follows government infrastructure projects knows that such predictions are likely to be off by a couple of million give or take), but then we came to the crux of our analysis – the environmental costs. Even estimating the impacts themselves was hard – How much rainforest would really be lost due to drilling? The only plans we could find were those from the oil companies that, of course, promised minimal damage due to ecologically sensitive extraction methods, but can you really trust these predictions, coming from somebody with a clear conflict of interest?

Furthermore, how do you value the loss of, say, 2’000 hectares of the most biodiverse rainforest currently in existence? Environmental economics has come up with several valuation methods (such as asking people how much they would value a particular area, or trying to come up with replacement costs people would need to pay if the ecosystem couldn’t provide its current services), but they are all flawed in one way or another. On the other hand, if you decide something is ‘invaluable’, this either means that no action altering it should be permitted, or it finally doesn’t enter economically driven cost-benefit analyses and is likely to be ignored.

Finally, we borrowed numbers from a valuation undertaken by the Earth Economics think tank and found that our project yielded a net loss when taking their higher-end estimate and a net benefit if taking their lower-end projection of the worth of the Yasuni. As I said – it depends.

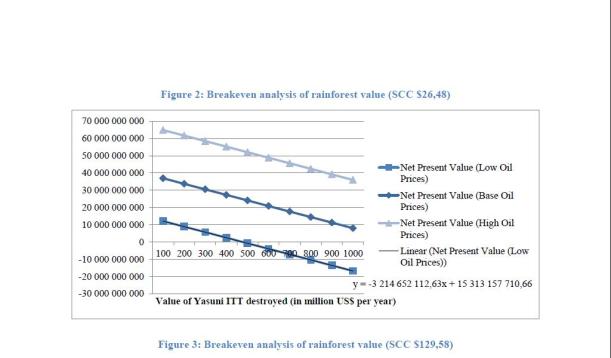

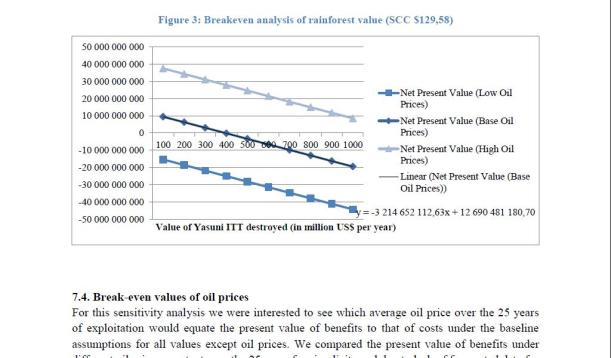

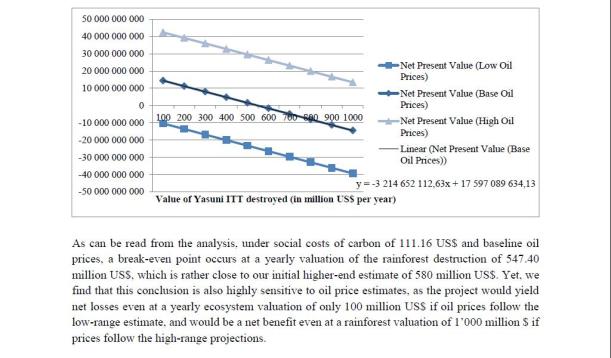

More interesting, maybe, was our sensitivity analysis that looked at the worth the rainforest would need to have for the project to break even, aka turn from net benefit into net loss. Have a look at these graphs:

We can see that the yearly value of Yasuni’s ecosystem services (accumulated over our timeline of 300 years and discounted in a time-declining fashion) would have to hover around 540 million US$ for the project to break even in our baseline scenario. But change oil prices up or down and it suddenly becomes a beneficial – or costly – project at any rainforest value!

We also repeated the analysis with different social costs of carbon – we calculated how much it would ‘cost’ the world in economic and climate change terms to burn the fossil fuels currently in the ground in the Yasuni, and took different estimations of the total cost of carbon to society. There is actually a fascinating academic debate out there right now – which I won’t get into but read this paper if you are interested – on the right value of carbon. Our baseline estimate follows the Stern Report, but if you take the number that is often used by governments, around 20 to 30 US$/ton of CO2 emitted, you suddenly get a beneficial project again. Le sigh.

Anyway, you can download our paper in a pdf format if you click on this link: Cost-BenefitAnalysisYasuni. I’d be delighted to get in touch with anybody interested in our methodology or who would like to look at our calculations. And thanks for appropriately citing it if you decide to use it further!