If you were asked to design an efficient, responsive, economical system to deliver food aid to poor people in a hunger crisis due to food price spikes, how would you do it?

a) Buy grain from your country’s farmers, put it on big boats, ship it across an ocean, hire some trucks, drive the trucks across a continent, circumvent the rebels that try to steal/blow up your trucks, and finally give out the food to the people that started to be hungry months ago.

b) Use the same money to buy vouchers or give cash transfers to the hungry people so that they can buy the more expensive food (that is locally produced, fits their diets and their nutritional needs) in the markets. Done!

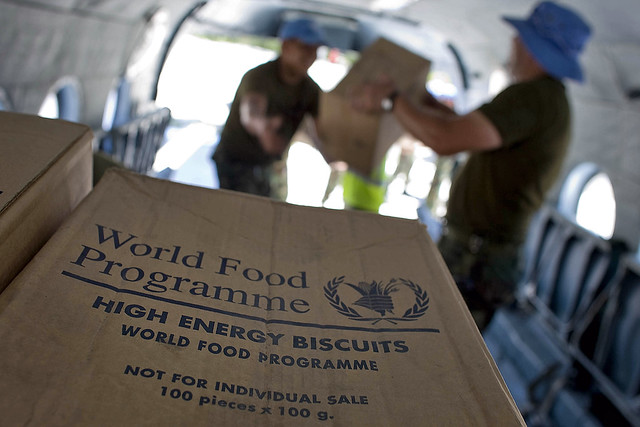

Image by UN Photo/Logan Abassi, via Flickr CC.

I’ll let you think about it a minute. Well? It should come as no surprise that option b) is the quicker and more effective way to fight hunger crises in situations where the problem is food affordability, not food availability*. And after 50 years stuck with formula a), it seems that U.S. policy makers have figured this out as well! The Obama administration in its 2014 budget is suggesting a major overhaul of its food aid policy, promising to make it more efficient, fair and responsive.

But let’s start at the beginning. More precisely, in the 1950s. This is when U.S. food aid policy started up during the reconstruction efforts in Europe and Asia, delivering U.S.-grown grains to the war-ravaged continents. In 1967, this position was reinforced in the first international food aid convention – and was left practically unchanged ever since.

From a U.S. perspective, the strategy appeared to be a win-win at first: they were helping another nation, but by paying U.S. farmers for their grain, hiring U.S. shipping companies for the transport, and U.S. logistical firms for the handling, they were able to support their own industry even more. This was especially vital in the periods of overproduction, when food aid policy was used as a quasi-export support mechanism to buy up the excess grain U.S. farmers were producing and keep prices high enough for them domestically. (European countries did the same thing, by the way).

This strategy however was widely criticized for its side-effects: in many instances, the food crises originated in local food prices sky-rocketing, making food no longer affordable for the poor – but there were still local producers selling goods on the markets! Once food aid donors swamped the markets with their own, free commodities, they drove local producers out of business – destroying previously functioning markets in the process and prolonging the crisis through their intervention themselves.

Additionally, it was a particularly cumbersome process that could take months to reach the food aid recipients and that was loaded with unnecessary expenses – from the higher U.S. food prices (compared to local procurement) to the entire logistical and shipping operations. Oxfam estimates that the final in-country value of U.S. food aid is less than 50% of the total, while the rest of the money is spent on shipping and procurement costs.

On the other hand, purchasing food in the region, using cash transfer and/or voucher options – where appropriate – has a number of advantages: it is more economical, faster, and supports the development of resilient local agricultural system. Plus, it is easier to address nutritional deficiencies (e.g. through allowing access to fresh produce rather than dry bulk imports). They also have the double benefit of supporting job creation in the agricultural and market sectors. Finally, as Eric Munoz from Oxfam explains,

“We can set up these systems very quickly, we can get resources to people in need very efficiently, and we can do it in a way that maintains some of the same, or increases, the accountability of the system to ensure that the people we are trying to aid actually are the recipients of the aid and that it doesn’t get syphoned off.”

Thus, the EU and more recently Canada have both moved to a policy in which local procurement, cash transfers and voucher distribution are some of the preferred responses to food crises, and can be used in addition or instead of in-kind food aid where appropriate. On the other hand, up to now only option a) from above is allowed as a food aid strategy in the United States.

Now the Obama administration is trying to follow the EU’s steps: according to proposed legislation, local procurement and food vouchers will be among the tools the U.S. Agency for International Development can use to address food crises in addition to the continued purchase of U.S. food aid. The White House has proposed this significant shift in its overseas policy to Congress and is hoping to convince policy-makers that this win-win for the U.S. development budget and the aided regions rings stronger than the agricultural lobby which will try to keep the current policy in place.

Do you think that Congress will follow the administration’s suggestion? What is your stance on the current overseas policy?

Bonus: Here are some fun facts for you – traditionally, the U.S. has accounted for around 50% of global food aid, whereas Europe has provided 27%, and the United States are also the main contributor to the World Food Programme (with 45% of its donations). In 2014, the government is asking for $1.8 billion to fund foreign food aid.

*And as a disclaimer – there are always instances where direct food distribution is necessary, if adverse weather conditions have wiped out the harvest of an entire region, for example. However, even then market mechanisms might be considered in addition to straight-up food provision.

I am pleased to note that WFP has a pilot project in several African and Latin American countries, purchasing local staples from small farmers in the affected countries. It is a more costly proposition, but leaves greater benefits in-country. Partially funded by the Howard Buffett Foundation, the Purchase for Progress project is definitely an interesting option.

Let’s hope that Congress passes the policy change so that such projects can be supported by the U.S. as well!

I think that this is an excellent idea but I’m not sure that the US businesses who are profiting from the transportation/shipping costs would agree. I am curious to see how this plays out! Thanks for such an interesting post!

Yeah there will definitely be a battle in Congress about it. Thanks for stopping by!