When you think about the linkage between food policy and public health, your first thought is probably over- or undernutrition, obesity, or diabetes – something relating the food we eat to our health directly. What if I told you that specifically livestock production methods could pose a health threat to us all, irrespective of where we live or whether we even eat meat?

Public health scholars have increasingly called for public attention to the use of antibiotics and other drugs as animal feed ingredients because of the possible direct and indirect impacts on global health as a whole. Let’s walk through what they are worried about:

- In many countries, antibiotics are used in animal production in a multitude of ways – for the treatment of sick animals, the control of the spreading of diseases in a flock of animals, the prevention of disease, but also for growth promotion and feed conversion (the rate at which animals transform feed into protein). In the US, 80% of antibiotics are sold for use in food animal production; in China, it’s 50%. On the other hand, in 2006 the EU banned antibiotic use for growth promotion purposes, as did South Korea in 2011.

- In disease prevention, feed conversion or growth promotion purposes, very low doses of antibiotics are used compared to when actual sick animals (or sick humans) are treated. In addition, these drugs are used continuously over a long duration of time, in the same location, and are often administered through feed and water (a 2009 study found that in the U.S. 74% of antibiotics were administered through feed, 16% through water and only 10% through more direct targeting of sick animals) – which means that exposure rates vary by animal depending on how much it eats or drinks.

- Ok, now comes the nitty gritty public healthy – antibiotic resistance. In administering antibiotics, you usually have a clear goal – to kill all bacteria. Now, there are several ways for bacteria to survive this, the most relevant one in this case being resistance selection: one bacteria will have a random genetic mutation, therefore be slightly different and will not be killed by the administered dose. Thus, it survives the antibiotic killing spree and happily reproduces more resistant bacteria. There is also horizontal gene transfer, where bacteria can share genes useful for survival, including those they don’t even need directly, and bacterial altruism, where drug-resistant bacteria share chemical signals with non-resistant ones to signal that they can help them out (it’s a pretty fascinating topic in itself…).

- Now we see why appropriate doses of antibiotics are so important – a quick and intense administration of one particular antibiotic will fulfill its purpose and kill the great majority of bacteria. However, the dosing imprecision that comes from administering antibiotics through feed is likely to lead to either over- or underexposure. If a particular animal is overexposed, it might lead to animal toxicity or drug residues in meat or milk, though that is uncommon. Much more common is underexposure or inconsistent exposure which leads to the bacterial resistance discussed above – the lower the antibiotics dose, the more bacteria with developing resistance will survive and procreate.

- How do we get from there to public health concerns? Well, there are a multitude of ways in which resistant bacteria can be carried from the farms into the general community – through farm workers (which often don’t have access to any protection equipment), the delivery trucks, air- and waterways, manure lagoons… Also, as much as 75% of administered antibiotics are not absorbed by the animals and just eliminated in waste, which is then often used as manure and applied on fields where it enters the crop production system.

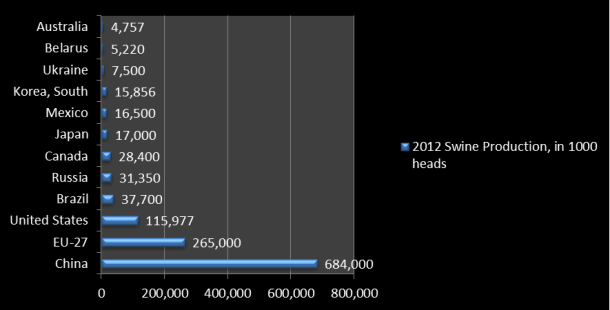

Once antibiotic resistance emerges, it is much more difficult (and costly) to treat human (and animal) illness, and since in many countries there is no clear differentiation between strictly human and strictly animal antibiotics, resistance in one field has huge impacts on the other. Recently, there has been increased attention on China as the largest producer and consumer of antibiotics in the world – a study found that close to animal production facilities, three times more antibiotic resistance genes were found than in other parts of the country.

One thing you can do: Buy organic meat! Most synthetic veterinary drugs are prohibited under organic regulations, including antibiotics and drug hormones. While this doesn’t really change your risk of exposure to resistant bacteria, you are helping to change the system.

Bonus: For a great overview of regulatory efforts, see this post, and this report seems to have a plethora of important information on the current animal farming system.

Hi Janina. I’ve read a lot on this particular topic myself. If you haven’t already (and would like to), make sure you get your hands on “Eating Animals” by Jonathan Safran Foer. It is a great and provoking read.

Oh I loved it! I was originally a little apprehensive (I am already a vegetarian and wasn’t sure whether I “needed” the persuasion) but it’s such a great literary achievement at the same time! I love how he tied in socio-cultural factors and philosophical points as well. Thanks for making me think back on it =)

Thanks for the marvelous posting! I definitely enjoyed reading it, you happen to be a great author.

I will remember to bookmark your blog and definitely will come back later in life.

I want to encourage you to continue your great posts, have

a nice afternoon!